|

Hamburgers - Hot Dogs - Nostalgia About - Scrapbook - Top Hat Gallery Guestbook - News - Contact |

|

Food Fight

Iconic Top Hat Burger Palace in battle for its lifeby Lisa McKinnon lmckinnon@VenturaCountyStar.com Ventura County Star; October 16, 2005 It's just a chili cheese dog, a simple dish of indeterminate pedigree. So why are Venturans having such a hard time letting go? The answer may lie not with the hot dog itself but with where it comes from -- in this case an 8-by-22-foot shack called the Top Hat Burger Palace.

Now that the neighborhood is being remade to better serve an ever-growing population amid pedal-to-the-metal real estate prices, that same corner is being eyed as the future address for a mixed-use housing development. As envisioned by Downtown Ventura Properties LLC, a group that includes longtime Ventura resident and developer James Mesa, the new, four-story building would feature subterranean parking, shops on the ground floor and, above that, 32 flats and townhomes arranged around and looking down onto a second-floor courtyard. It would not, however, include the Top Hat. This news came as something of a surprise to those who assumed the Top Hat was an official landmark, if not on its own merits then perhaps through its largely forgotten connection to a 1989 murder trial that used the then-newfangled concept of DNA evidence. In response to the ensuing public outcry, the Ventura City Council in July asked city staff to look into the feasibility of moving the burger stand, perhaps to a small park on California and Santa Clara streets. But on Oct. 4, a special joint meeting of the city's planning commission and historic preservation committee had a very different result. This time, the developers were asked to go back to the drawing board and devise a plan that would "embrace" rather than move or exclude the Top Hat. On its own, the burger stand is not a significant building, said planning commission vice chairperson Curtis Stiles, who went so far as to call it "raggedy-looking." But "it is a significant place," one worthy of keeping in some form or another, he said. Mesa agrees, to a point. Last year, he offered Top Hat owner Charlotte Bell and her grandson, Jack Bell, a chance to join the development project, albeit in a space around the corner, facing Palm Street. The Bells passed on the idea. "I wasn't thinking of having any other restaurants in the new place, just the Top Hat, out of admiration for its history and staying power," Mesa said. But he also wants to bring in businesses that will attract more foot traffic to the area, reviving a sense of downtown vibrancy that "got lost in the 1960s," he added. "It would be great to have something there that comes alive at night."

Focus on the foodies "Top Hat has an eclecticism that can never be duplicated, an ambience you can't get out of an image manual. It's one of those places you find in quirky guide books. "It's a place you seek out, the Pink's of Ventura," he added, referring to the Hollywood hot dog stand founded in 1939 by Paul Pink. Baker grew up in the Riverside County town of Corona and visited Ventura during numerous childhood road trips with his family. Today, he makes a point of stopping in whenever he's on Highway 101 between Santa Barbara and Los Angeles. Top Hat is a major draw on his sentimental journey. Baker likes how regulars are greeted by their nicknames, and the way orders are tallied on a clipboard instead of a cash register. The chili dogs aren't bad, either. "You get familiar with places, form an emotional attachment," he said. "Maybe it starts with the food." It was that sort of thinking that encouraged Baker to explore the idea of "foodie" tourism for the San Francisco Convention & Visitors Bureau. There, he created programs to attract the kind of travelers who think nothing of driving more than 50 miles, one way, to sample the menu at an unusual restaurant or to savor the flavor of a locally grown strawberry. Studies have shown that these culinary tourists tend to stay longer and spend more money compared to their garden-variety cousins. In other words, they are catnip to groups like the Ventura Visitors and Convention Bureau, which in January 2004 presented a culinary-tourism seminar led by Baker. The bureau also produces a bimonthly newsletter called The Dish for food-minded visitors, and has listed the Top Hat in media releases touting the emergence of downtown "as a destination for both global cuisine and sophisticated dining." But what Baker calls "foodie-ism" isn't limited to white tablecloths and formality. "It's about discovering something that is new or different," he said. "Foodies want to have an authentic experience. So does everyone else."

Chain reactions "Even if there are only three people a year who stop in Ventura specifically to eat at the Top Hat, those people are not going to stop there to eat at a Subway. "Take the Ventura mission. Now tear it down and put a generic, modern church there. You'll still get people going to church, but you won't get people making pilgrimages to the mission," added Andrews. "It's another thing gone missing, making the city look like every other city," he said. "Pretty soon, you find yourself asking: 'Are we in Oxnard? Are we in Santa Paula?' "

Preventing identity theft In Manhattan, the 121-year-old saloon P.J. Clarke's was deemed such a fixture that a 45-story skyscraper was built behind it rather than in its place. The restaurant remains as famous for its oyster samplers and chicken pot pies as it is for its permanently out-of-order pay phone and busted cigarette machine. Closer to home, in Glendale, city officials and the Los Angeles Conservancy are working together to save what they can of Algemac's Coffee Shop, which sits on property slated for a new housing development. The building dates to the 1920s, but the coffee shop was remodeled in 1958 by MGM set designer Ralph Vaughn in an architectural style called Googie. The name comes from a chain of "Jetsons"-like coffee shops designed in the late 1940s by John Lautner. Like Googie, the "roadside vernacular" style of Irv's Burgers in West Hollywood (and of Top Hat in Ventura) is a form of architecture that previous generations took for granted or considered outright junk. It has since found a place in the sentimental hearts of baby boomers and in the ironic retroism of Generations X and Y. In September, the West Hollywood City Council agreed to designate Irv's Burgers as a "cultural resource," saving the stand, but not necessarily the current tenants, for Generations Z and beyond. Jay's in Silverlake has not been so lucky. Caught in a dispute between the family of its founder, who topped each Jayburger with a fried egg, and the owners of the land on which the burger shack stands, the business was fenced off earlier this year to facilitate the construction of a new mini mall on an adjacent lot. The property owners have vowed to keep the shack in place, perhaps because tearing it down would require them to give up some of the lot for the widening of a nearby intersection. Top Hat's future raises similarly complicated issues. Owned since 1966 by members of the Bell and McKee families, it hews to the health and safety regulations of an earlier time. Moving it would break that spell, unleashing a wave of contemporary-code requirements. Allowing the Top Hat to stay would sidestep those requirements only until such time as the family leaves the business. Jack Bell hopes that won't be happening anytime soon. About a month ago, he installed an ATM swiper on Top Hat's red metal counter, the better to handle new customers clamoring for chili dogs but unfamiliar with the burger stand's cash-only operations. "We've been here so long, if we had to move it wouldn't feel normal. Whatever normal is," Bell said. Copyright © 2005 by Ventura County Star

|

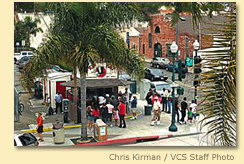

Crafted from wood and sheets of metal that could date back to World War II, the Top Hat is an institution to some, an eyesore to others. But undisputed is the fact that, for more than 50 years, some version of the Top Hat has served chili-covered dogs, burgers and fries from its spot on the northwest corner of Main and Palm streets in downtown Ventura.

Crafted from wood and sheets of metal that could date back to World War II, the Top Hat is an institution to some, an eyesore to others. But undisputed is the fact that, for more than 50 years, some version of the Top Hat has served chili-covered dogs, burgers and fries from its spot on the northwest corner of Main and Palm streets in downtown Ventura.